Cosmic rays are energetic particles originating from space that impinge on Earth's atmosphere. Almost 90% of all the incoming cosmic ray particles are protons, about 9% are helium nuclei (alpha particles) and about 1% are electrons. Note that the term "ray" is a misnomer, as cosmic ray particles arrive individually, not in the form of a ray or beam of particles. See wave-particle duality.

The kinetic energies of cosmic ray particles span over fourteen orders of magnitude, with the flux of cosmic rays on Earth's surface falling approximately as the inverse-cube of the energy. The wide variety of particle energies reflects the wide variety of sources. Cosmic rays originate from energetic processes on the Sun all the way to the farthest reaches of the visible universe. Cosmic rays can have energies of over 10

Cosmic ray sources

Solar cosmic rays are cosmic rays that originate from the Sun, with relatively low energy (10-100 keV or 1.6 - 16 fJ per particle). The average composition is similar to that of the Sun itself.

The name solar cosmic ray itself is a misnomer because the term cosmic implies that the rays are from the cosmos and not the solar system, but it has stuck. The misnomer arose because there is continuity in the energy spectra, i.e., the flux of particles as a function of their energy, because the low-energy solar cosmic rays fade more or less smoothly into the galactic ones as one looks at increasingly higher energies.

Galactic cosmic rays

See Extragalactic cosmic ray.

Extragalactic cosmic rays

See Ultra-high-energy cosmic ray.

Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays

Anomalous cosmic rays (ACRs) are cosmic rays with unexpectedly low energies. They are thought to be created near the edge of our solar system, in the heliosheath, the border region between the heliosphere and the interstellar medium. When electrically neutral atoms are able to enter the heliosheath (being unaffected by its magnetic fields) subsequently become ionized, they are thought to be accelerated into low-energy cosmic rays by the solar wind's termination shock which marks the inner edge of the heliosheath. It is also possible that high energy galactic cosmic rays which hit the shock front of the solar wind near the heliopause might be decelerated, resulting in their transformation into lower-energy anomalous cosmic rays.

The Voyager 1 space probe crossed the termination shock on December 16, 2004, according to papers published in the journal Science. Readings showed particle acceleration, but not of the kind that generates ACRs. It is unclear at this stage (September 2005) if this is typical of the termination shock (requiring a major rethink of the origin of ACRs), or a localised feature of that part of the termination shock that Voyager 1 passed through. Voyager 2 is expected to cross the termination shock during or after 2008, which will provide more data.

Anomalous cosmic rays

Anomalous cosmic raysCosmic rays may broadly be divided into two categories, primary and secondary. The cosmic rays that arise in extrasolar astrophysical sources are primary cosmic rays; these primary cosmic rays can interact with interstellar matter to create secondary cosmic rays. The sun also emits low energy cosmic rays associated with solar flares. The exact composition of primary cosmic rays, outside the Earth's atmosphere, is dependent on which part of the energy spectrum is observed. However, in general, almost 90% of all the incoming cosmic rays are protons, about 9% are helium nuclei (alpha particles) and about 1% are electrons. The remaining fraction is made up of the other heavier nuclei which are abundant end products of star's nuclear synthesis. Secondary cosmic rays consist of the other nuclei which are not abundant nuclear synthesis end products, or products of the big bang, primarily lithium, beryllium and boron. These light nuclei appear in cosmic rays in much greater abundance (about 1:100 particles) than in solar atmospheres, where their abundance is about 10

Composition

The flux (flow rate) of cosmic rays incident on the Earth's upper atmosphere is modulated (varied) by two processes; the sun's solar wind and the Earth's magnetic field. Solar wind is expanding magnetized plasma generated by the sun, which has the effect of decelerating the incoming particles as well as partially excluding some of the particles with energies below about 1 GeV. The amount of solar wind is not constant due to changes in solar activity over its regular eleven-year cycle. Hence the level of modulation varies in autocorrelation with solar activity. Also the Earth's magnetic field deflects some of the cosmic rays, which is confirmed by the fact that the intensity of cosmic radiation is dependent on latitude, longitude and azimuth. The cosmic flux varies from eastern and western directions due to the polarity of the Earth's geomagnetic field and the positive charge dominance in primary cosmic rays; this is termed the east-west effect. The cosmic ray intensity at the equator is lower than at the poles as the geomagnetic cutoff value is greatest at the equator. This can be understood by the fact that charged particle tend to move in the direction of field lines and not across them. This is the reason the Aurorae occur at the poles, since the field lines curve down towards the Earth's surface there. Finally, the longitude dependence arises from the fact that the geomagnetic dipole axis is not parallel to the Earth's rotation axis.

This modulation which describes the change in the interstellar intensities of cosmic rays as they propagate in the heliosphere is highly energy and spatial dependent, and it is described by the Parker's Transport Equation in the heliosphere. At large radial distances, far from the Sun ~ 94 AU, there exists the region where the solar wind undergoes a transition from supersonic to subsonic speeds called the solar wind termination shock. The region between the termination shock and the heliospause (the boundary marking the end of the heliosphere) is called the heliosheath. This region acts as a barrier to cosmic rays and it decreases their intensities at lower energies by about 90% indicating that it is not only the Earth's magnetic field that protect us from cosmic ray bombardment. For more on this topic and how the barrier effects occur the agile reader is referred to Mabedle Donald Ngobeni and Marius Potgieter (2007), and Mabedle Donald Ngobeni (2006). From modelling point of view, there is a challenge in determining the Local Interstellar spectra (LIS) due to large adiabatic energy changes these particles experience owing to the diverging solar wind in the heliosphere. However, significant progress has been made in the field of cosmic ray studies with the development of an improved state-of-the-art 2D numerical model that includes the simulation of the solar wind termination shock, drifts and the heliosheath coupled with fresh descriptions of the diffusion tensor, see Langner et al. (2004). But challenges also exist because the structure of the solar wind and the turbulent magnetic field in the heliosheath is not well understood indicating the heliosheath as the region unknown beyond. With lack of knowledge of the diffusion coefficient perpendicular to the magnetic field our knowledge of the heliosphere and from the modelling point of view is far from complete. There exist promising theories like ab initio approaches, but the drawback is that such theories produce poor compatibility with observations (Minnie, 2006) indicating their failure in describing the mechanisms influencing the cosmic rays in the heliosphere.

Modulation

The nuclei that make up cosmic rays are able to travel from their distant sources to the Earth because of the low density of matter in space. Nuclei interact strongly with other matter, so when the cosmic rays approach Earth they begin to collide with the nuclei of atmospheric gases. These collisions, in a process known as a shower, result in the production of many pions and kaons, unstable mesons which quickly decay into muons. Because muons do not interact strongly with the atmosphere and because of the relativistic effect of time dilation many of these muons are able to reach the surface of the Earth. Muons are ionizing radiation, and may easily be detected by many types of particle detectors such as bubble chambers or scintillation detectors. If several muons are observed by separated detectors at the same instant it is clear that they must have been produced in the same shower event.

Detection

When cosmic ray particles enter the Earth's atmosphere they collide with molecules, mainly oxygen and nitrogen, to produce a cascade of lighter particles, a so-called air shower. The general idea is shown in the figure which shows a cosmic ray shower produced by a high energy proton of cosmic ray origin striking an atmospheric molecule.

This image is a simplified picture of an air shower: in reality, the number of particles created in an air shower event can reach in the billions, depending on the energy of the primary particle. All of the produced particles stay within about one degree of the primary particle's path. Typical particles produced in such collisions are charged mesons (e.g. positive and negative pions and kaons); one common collision is:

Cosmic rays are also responsible for the continuous production of a number of unstable isotopes in the Earth's atmosphere, such as carbon-14, via the reaction:

Cosmic rays have kept the level of carbon-14 in the atmosphere roughly constant (70 tons) for at least the past 100,000 years. This an important fact used in radiocarbon dating which is used in archaeology.

Interaction with the Earth's Atmosphere

There are a number of cosmic ray research initiatives. These include, but are not limited to:

CHICOS

PAMELA

Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer

MARIACHI

Pierre Auger Observatory

Spaceship Earth Research and experiments

After the discovery of radioactivity by Henri Becquerel in 1896, it was generally believed that atmospheric electricity (ionization of the air) was caused only by radiation from radioactive elements in the ground or the radioactive gases (isotopes of radon) they produce. Measurements of ionization rates at increasing heights above the ground during the decade from 1900 to 1910 showed a decrease that could be explained as due to absorption of the ionizing radiation by the intervening air. Then, in 1912, Victor Hess carried three Wulf electrometers (a device to measure the rate of ion production inside a hermetically sealed container) to an altitude of 5300 meters in a free balloon flight. He found the ionization rate increased approximately fourfold over the rate at ground level. He concluded "The results of my observation are best explained by the assumption that a radiation of very great penetrating power enters our atmosphere from above." In 1913-14, Werner Kolhörster confirmed Victor Hess' results by measuring the increased ionization rate at an altitude of 9 km. Hess received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1936 for his discovery of what came to be called "cosmic rays".

For many years it was generally believed that cosmic rays were high-energy photons (gamma rays) with some secondary electrons produced by Compton scattering of the gamma rays. Then, during the decade from 1927 to 1937 a wide variety of experimental investigations demonstrated that the primary cosmic rays are mostly positively charged particles, and the secondary radiation observed at ground level is composed primarily of a "soft component" of electrons and photons and a "hard component" of penetrating particles, muons. The muon was initially believed to be the unstable particle predicted by Hideki Yukawa in 1935 in his theory of the nuclear force. Experiments proved that the muon decays with a mean life of 2.2 microseconds into an electron and two neutrinos, but that it does not interact strongly with nuclei, so it could not be the Yukawa particle. The mystery was solved by the discovery in 1947 of the pion, which is produced directly in high-energy nuclear interactions. It decays into a muon and one neutrino with a mean life of 0.0026 microseconds. The pion→muon→electron decay sequence was observed directly in a microscopic examination of particle tracks in a special kind of photographic plate called a nuclear emulsion that had been exposed to cosmic rays at a high-altitude mountain station. In 1948, observations with nuclear emulsions carried by balloons to near the top of the atmosphere by Gottlieb and Van Allen showed that the primary cosmic particles are mostly protons with some helium nuclei (alpha particles) and a small fraction heavier nuclei.

In 1934 Bruno Rossi reported an observation of near-simultaneous discharges of two Geiger counters widely separated in a horizontal plane during a test of equipment he was using in a measurement of the so-called east-west effect. In his report on the experiment, Rossi wrote "...it seems that once in a while the recording equipment is struck by very extensive showers of particles, which causes coincidences between the counters, even placed at large distances from one another. Unfortunately, he did not have the time to study this phenomenon more closely." In 1937 Pierre Auger, unaware of Rossi's earlier report, detected the same phenomenon and investigated it in some detail. He concluded that extensive particle showers are generated by high-energy primary cosmic-ray particles that interact with air nuclei high in the atmosphere, initiating a cascade of secondary interactions that ultimately yield a shower of electrons, photons, and muons that reach ground level.

Homi Bhabha derived an expression for the probability of scattering positrons by electrons, a process now known as Bhabha scattering. His classic paper, jointly with W. Heitler, published in 1937 described how primary cosmic rays from space interact with the upper atmosphere to produce particles observed at the ground level. Bhabha and Heitler explained the cosmic ray shower formation by the cascade production of gamma rays and positive and negative electron pairs. In 1938 Bhabha concluded that observations of the properties of such particles would lead to the straightforward experimental verification of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity.

Measurements of the energy and arrival directions of the ultra-high-energy primary cosmic rays by the techniques of "density sampling" and "fast timing" of extensive air showers were first carried out in 1954 by members of the Rossi Cosmic Ray Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The experiment employed eleven scintillation detectors arranged within a circle 460 meters in diameter on the grounds of the Agassiz Station of the Harvard College Observatory. From that work, and from many other experiments carried out all over the world, the energy spectrum of the primary cosmic rays is now known to extend beyond 10 eV (past the GZK cutoff, beyond which very few cosmic rays should be observed). A huge air shower experiment called the Auger Project is currently operated at a site on the pampas of Argentina by an international consortium of physicists. Their aim is to explore the properties and arrival directions of the very highest energy primary cosmic rays. The results are expected to have important implications for particle physics and cosmology.

Three varieties of neutrino are produced when the unstable particles produced in cosmic ray showers decay. Since neutrinos interact only weakly with matter most of them simply pass through the Earth and exit the other side. They very occasionally interact, however, and these atmospheric neutrinos have been detected by several deep underground experiments. The Super-Kamiokande in Japan provided the first convincing evidence for neutrino oscillation in which one flavour of neutrino changes into another. The evidence was found in a difference in the ratio of electron neutrinos to muon neutrinos depending on the distance they have traveled through the air and earth.

History

Effects

Cosmic rays constitute a fraction of the annual radiation exposure of human beings on earth. For example, the average radiation exposure in Australia is 0.3 mSv due to cosmic rays, out of a total of 2.3 mSv.[1]

Role in Ambient Radiation

Understanding the effects of cosmic rays on the body will be vital for assessing the risks of space travel. R.A. Mewaldt estimated humans unshielded in interplanetary space receive annually roughly 400 to 900 mSv (compared to 2.4 mSv on Earth) and that a 30 month Mars mission might expose astronauts to 460 mSv (at Solar Maximum) to 1140 mSv (at Solar Minimum).

Due to the potential negative effects of astronaut exposure to cosmic rays, solar activity may play a role in future space travel via the Forbush decrease effect. Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) can temporarily lower the local cosmic ray levels, and radiation from CMEs is easier to shield against than cosmic rays.

Significance to Space Travel

Significance to Space TravelCosmic rays have been implicated in the triggering of electrical breakdown in lightning. It has been proposed (see Gurevich and Zybin, Physics Today, May 2005, "Runaway Breakdown and the Mysteries of Lightning") that essentially all lightning is triggered through a relativistic process, "runaway breakdown", seeded by cosmic ray secondaries. Subsequent development of the lightning discharge then occurs through "conventional breakdown" mechanisms.

Role in climate change

Because of the metaphysical connotations of the word "cosmic", the very name of these particles enables their misinterpretation by the public, giving them an aura of mysterious powers. Were they merely referred to as "high-speed protons and atomic nuclei" this might not be so.

In fiction, cosmic rays have been used as a catchall, mostly in comics (notably the Marvel Comics group the Fantastic Four), as a source for mutation and therefore the powers gained by being bombarded with them.

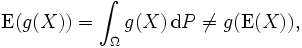

1984 photograph

1984 photograph which is not one of the possible outcomes.

which is not one of the possible outcomes.

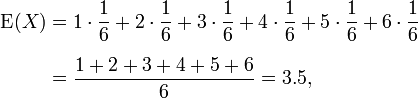

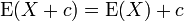

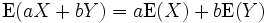

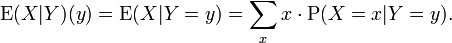

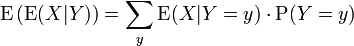

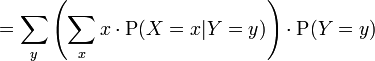

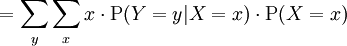

Properties

Properties

.

. is

is

is a function on

is a function on

and

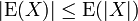

and  , the absolute value of expectation of a random variable is less or equal to the expectation of its absolute value:

, the absolute value of expectation of a random variable is less or equal to the expectation of its absolute value:

), and positive real number

), and positive real number

is not necessarily equal to

is not necessarily equal to  . If multiplicativity occurs, the

. If multiplicativity occurs, the

Types of handguns

Types of handguns